Reflections on CG Jung’s – Flying Saucers, A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Skies. Part 1

Introduction

As it is widely known, Carl Jung’s fields of study included many topics that could be considered outside of the traditional Psychology and Psychiatry areas. He was interested in understanding any field that impacted human consciousness and the psyche, including parapsychology and other phenomena in the fringes of human thought, and he never shied away of analyzing any topic with an open mind.

Perhaps one of his lesser known publications was the one related to the topic of Flying Saucers, phenomena that became popular in the culture during the mid 1940’s. Jung started collecting information on the subject around 1946, paying attention to newspaper reports, and all kinds of statements by dedicated study groups, and scientific and military authorities. As it was the case with any topic that interested Jung, he read every available book and opinion on the subject available at the time, and he became both curious and preoccupied with the subject. Jung wrote a letter to a friend in 1951, in which he mentioned the following:

“ I’m puzzled to death about these phenomena, because I haven’t been able yet to make out with sufficient certainty whether the whole thing is a rumor with concomitant singular and mass hallucination, or a downright fact. Either case would be highly interesting. If it’s a rumor, then the apparition of discs must be a symbol produced by the unconscious. We know what such a thing would mean seen from the psychological standpoint. If on the other hand, it is a hard and concrete fact, we are surely confronted with something thoroughly out of the way. At a time when the world is divided by an iron curtain – a fact unheard of in human history – we might expect all sorts of funny things, since when such a thing happens in an individual it means a complete dissociation, which is instantly compensated by symbols of wholeness and unity. The phenomenon of the saucers might even be both, rumor as well as fact. In this case it would be what I call a synchronicity. It’s just too bad that wo don’t know enough about it.” (Jung, 1964, p. vii).

These comments by Jung rise several interesting elements that are worth analyzing. First of all, we can immediately notice that Jung is taking this phenomena seriously, and considers that is a topic that is worth analyzing in more detail, even if it is just a rumor, in which case he points out that this could very well be ‘a symbol produced by the unconscious’, and gives a potential reason the dissociation possibly created in individuals due to the heavy stress generated by the global political conditions, particularly the recent implementation of the iron curtain that divides the world, and the beginning of the cold war. Per the Jungian view of the psyche behavior, when affected by heavy stress, the individual (and social) psyche might find a relief by dissociating, and finds compensation by looking (or creating) symbol of ‘wholeness and unity”. And as a second potential situation, Jung considers the possibility of having a synchronicity, in which the individuals are affected by the stress of global conditions AND these phenomena are also real physical elements appearing at the same time.

This paper will summarize the ideas that Jung presented in the early days of the “flying saucer” phenomena, providing with a clear example of Jung’s open mind and relentless curiosity to analyze and better understand all human psyche related conditions, even when most of the scientific and governmental establishments were unwilling to provide credibility to these events. We will also see how most of the ideas and conclusions provided by Jung are still valid today, and can still be applied as reference for further study.

Jung’s first interest in studying the “Flying Saucers” phenomena

From the early days of the appearance of the “flying saucer” phenomena in the mid 1940’s, Jung realized the psychological challenges that this situation presented. His main question, similar to most serious observers of the phenomena was “If these objects were real or if they are a mere fantasy product”; followed immediately by the questioning: “If they are real, exactly what are they? If they are fantasy, why should such a rumor exist?” (p. 3).

Jung describes how he came up with “an interesting and quite unexpected discovery”, resulting from his first article published on the subject in 1954, for the Swiss weekly Die Weltwoche. On this publication, Jung presented a skeptical point of view to the phenomena, but at the same time, he was respectful of the opinions provided by the large number of specialists that were given credibility to the subject. Four years later, in 1958, Jung’s article was discovered by the global media, and the information was widely spread, but was distorted to indicate that Jung was a “flying saucer believer.” Jung then issued a note of clarification mentioning his true skeptical opinion, but this clarification received no interest by the global press. This situation taught Jung the way curious way that people was reacting to the phenomena, and he indicates: “one must draw the conclusion that news affirming the existence of UFOs is welcome, but that skepticism seems to be undesirable. To believe that UFOs are real suits the general opinion, whereas disbelief is to be discouraged. This creates the impression that there is a tendency all over the world to believe in saucers and to want them to be real, unconsciously helped along by a press that otherwise has no sympathy with the phenomenon.” (p. 3).

This curious reaction was enough for Jung to merit his interest to study the flying saucers, and was the first reason for Jung to become interested in the subject, starting from his first question: “Why should it be more desirable for saucers to exist than not?”

The End of an Era

Immediately after deciding to engage in the study of “flying saucers” (this is the term widely used in the early days of the phenomena, and Jung uses it most of the time, although he also uses the term ‘UFOs’. Here I will use both terms following Jung’s method). Jung understood that this was a highly subjective phenomena, and similar to other studies he made, his main challenge was going to be how to apply scientific structures to bring this phenomena into the formal academia and science umbrella. He mentions: “These rumors, or the possible physical existence of such objects, seem to me so significant that I feel myself compelled, as once before (*) when events of fateful consequence were brewing for Europe, to sound a note of warning. I know that, just as before, my voice is much too weak to reach the ear of the multitude. It is not presumption that drives me, but my conscience as a psychiatrist that bids me fulfil my duty and prepare those few who will hear me for coming events which are in accord with the end of an era.” (Jung, 1964, p. 5).

In regards to the end of an era, Jung is referring to the ancient Egyptian and Greek history that calls for “psychic changes that occur at the end of a Platonic month and the beginning of another,” generating “changes in the constellation of psychic dominants, of the archetypes or ‘gods’ as they used to be called, which bring about, or accompany, long lasting transformation of the collective psyche.” He is referring to the change from the rise of Christianity, or the era of Pisces, and how humanity was nearing the great change when entering the age of Aquarius, sometime around the end of the 20th Century and the beginning of the 21st Century.

On an interview for Die Weltwoche in 1954, Jung aligns his conclusions of the phenomena with those of Edward J. Ruppelt, the chief of the American Air Force’s project for investigation of UFO reports, which determines that “something is seen, but one doesn’t know what.” But the next comment raises quite an important element: “It is difficult, if not impossible, to form any correct idea of these objects because they behave not like bodies, but like weightless thoughts.” (Jung, 1964, p. 6). This surprising conclusion comes from the fact that some objects that are observed are supported with radar signatures, but many of the visual observations are not detected by the radar systems, therefore questioning their physical existence. This definition of “weightless thoughts” has very important ramifications that extend until recent theories, and is particularly impactful, given the myriad of further observations that somehow appear to support the possibility that the objects behave with what appears to be a tight connection to observer’s thoughts and consciousness. It seems that Jung brought up early some level of engagement existing between the objects early called “flying saucers” and human consciousness.

Keeping with Jung’s consideration of the apparent connection of these objects and human consciousness, he points out that “the longer the uncertainty lasted, the greater became the probability that this obviously complicated phenomenon had an extremely important psychic component as well as a possible physical basis.” And also, Jung indicates: “Such an object provokes, like nothing else, conscious and unconscious fantasies, the former giving rise to speculative conjectures and pure fabrications, and the latter supplying the mythological background inseparable from these provocative observations. Thus there arose a situation in which, with the best will in the world, one often did not know and could not discover whether a primary perception was followed by a phantasm or whether, conversely, a primary fantasy originating the unconscious invaded the conscious mind with illusions and visions.” (Jung, 1964, p. 7). Indeed, the fact that this phenomenon combines conscious and unconscious elements, it is not possible, at least for now, to identify its origin, being potentially first some type of physical observation that generates an unconscious reaction that helps build up and strengthen the effect, or vice-versa, if a fantasy based element of the unconscious gives an opening for the psyche to build up some type of physical reality. As most of Jung’s ideas and reflections, this concept appears to be quite ahead for its time, and resonate even with today’s theories of the UAP phenomenon. Reflecting in more detail on Jung’s reflections by mid 20th Century, we will see that the knowledge of the UAP phenomenon has not advanced that much, and remains as much a mystery as it was in Jung’s times. In addition to the two possible situations identified by Jung, he also adds the possibility that these two conditions could be tied via a synchronicity, which means that this events could be meaningful coincidences that connect a physical phenomenon with an archetypal psychic process.

Perhaps the most important point that we find here is that Jung at no point questions the credibility of the experiencers of the “flying saucer” phenomena, and he identifies potential sources, both physical and psychical that deserve further analysis and detailed study. As we will see more and more through this analysis of Jung’s work, we will find that after more than 60 years, the phenomena still remains a mystery, no matter the advances in human science and technology.

Jung’s Initial Analysis of the UFO’s as Rumors

Very early in Jung’s analysis, he recognizes that there is not much that he can offer to evaluate the UFO phenomena as a potential physical reality. He understands that this analysis of material elements needs to be led by the scientific community, using its measurement and test techniques. However, Jung sees his value added in analyzing the phenomena by studying its psychic aspects, and the psychological elements that generate that such a phenomena can grow and expand in society, starting from specific rumors.

The first real situation of the phenomena is that whether physical or psychical, it is already expanded and continues to rapidly expand in the different regions of the world. The natural assumption if the phenomena has a material reality is to reject it, and consider that is the result of somebody’s illusions, fantasies, or lies. Clearly people that make these types of reports must have something wrong in their heads!

If we follow this line of thought, the next step is to consider that the phenomena is based on stories and rumors, which must have a psychical source rather than a material source.

The difference, however, with mere rumors, is that these phenomena appear to have a basis on people’s visions, which Jung calls “a visionary rumor.” To explain this, Jung mentions that this type of rumor “is closely akin to the collective visions of, say, the crusaders during the siege of Jerusalem, the troops at Mons in the first World War, the faithful followers of the pope at Fatima, Portugal, etc. Apart from collective visions, there are on record cases where one or more persons see something that physically is not there.” (p. 8).

All of these examples of collective visions have a very strong numinous, psychical and spiritual basis, such that large groups of people end up directly observing certain objects and visual effects. Jung, however, even if he does not question or rejects these events, he also points out that “Even people who are entirely compos mentis (having control/mastery of one’s mind) and in full possession of their senses can sometimes see things that do not exist.” (p. 9). The difference with visionary rumors is that they need to include some level of “unusual emotion” and the reason why they grow into visions or delusions has a source of stronger excitations, therefore, have their origin on a deeper source.

The first sources considered for this phenomenon occurred during the second half of World War II. First with the observation of mysterious projectiles and rockets in Sweden, which were attributed to the Russians; and second with the so called “foo fighters” or lights that flew closely to the allied bombers over Germany, but then finding out that these objects were also following the German airplanes. In both cases, the real sources of these two events were never clarified. After the first use of atomic bombs, in 1945, the sightings started occurring immediately in the United States. Due to inability to identify an earthly origin for the objects, and also not understanding how the objects were able to demonstrate such amazing performance abilities, the rumor grew to include the assumption that the objects had an extra-terrestrial origin, and even to represent a possible threat to humanity. Jung describes: “The motif of an extraterrestrial invasion was seized upon by the rumor, and the UFO’s were interpreted as machines controlled by intelligent beings from outer space. The apparently weightless behavior of spaceships and their intelligent, purposive movements were attributed to the superior technical knowledge and ability of the cosmic intruders….It also seemed that airfields and atomic installations in particular held a special attraction for them, from which it was concluded that the dangerous development of atomic physics and nuclear fission had caused a certain disquiet on our neighboring planets and necessitated a more accurate survey from the air.” (p. 11).

Regardless of their apparent focus on military installations, Jung recognizes that: “Nobody really knows what they are looking for or want to observe…Their flights do not appear to be based on any recognizable system. They behave more like groups of tourists unsystematically viewing the countryside, pausing now here for a while and now there, erratically following first one interest and then another….” (p. 11)

Jung’s summary of the “flying saucer” phenomena as appeared in the 1950’s is quite complete, and once again, the details he indicates are very close to descriptions that can be found today. Jung continues his summary of the descriptions at the time by saying: “Sometimes they appear to be up to five hundred yards in diameter, sometimes small as electric street-lamps. There are large mother ships from which little UFO’s slip out or in which they take shelter. They are said to be both manned and unmanned, and in the latter case are remote controlled. According to the rumor, the occupants are about three feet high and look like human beings or, conversely, are utterly unlike us. Other reports speak of giants fifteen feet high. They are beings who are carrying out a cautios survey of the earth and considerately avoid all encounters with men or, more menacingly, are spying out landing places with a view to settling the population of a planet that has got into difficulties and colonizing the earth by force. Uncertainty in regard to the physical conditions on earth and their fear of unknown sources of infection have held them back temporarily from drastic encounters and even from attempted landings, although they possess frightful weapons which would enable them to exterminate the human race. In addition to their obviously superior technology they are credited with superior wisdom and moral goodness which would, on the other hand, enable them to save humanity.” (p. 11).

While Jung was eager here to provide the most complete description available for the phenomenon by then. He maintained a healthy skepticism about the popular assumptions held at the time. He recognizes that the rumors of the time, particularly related to the physical elements of the events, contain “the essentials for an unsurpassable ‘science-fiction story’” (p. 12) but, while keeping himself up to date on all the reports published globally, he continued to leave the physical portions of the phenomenon to the aerospace experts, and he continued his focus on the psychical source and its impact in the human consciousness. His thoughts at this time recognize the existence of thousands of UFO reports, and their impact in generating the “visionary rumor”, which objectively analyzed make room for an “impressive collection of mistaken observations and conclusions into which subjective psychic assumptions have been projected.” (p. 12). Is on these projections that Jung focuses his analysis, using his expertise on the human psyche and the development of myths and mind-generated effects.

Psychological Projections as Potential Sources of the UFO Phenomenon

In order for the phenomenon to be a result of a psychological projection, it requires a psychical cause. Jung recognizes that given the worldwide incidence of these observations must mean that the phenomenon has an “extensive causal basis”; and the first conclusion should be that “When an assertion of this kind is corroborated practically everywhere, we are driven to assume that a corresponding motive must be present everywhere too.” (p. 13).

The ’visionary rumors’ that Jung mentions, may originate from external sources and circumstances, but they need a basis of “an omnipresent emotional foundation” which given the reach of this phenomenon must be a “psychological situation common to all mankind.” Therefore, Jung concludes here that “The basis for this kind of rumors an emotional tension having its cause in a situation of collective distress or danger, or in a vital psychic need.” (p. 13).

Given the geo-political situation in the world in the mid 20th Century, Jung believes that the specific condition generating strain in the world population is a result of the policies and behavior of the Soviet Union, and their unpredictable consequences. The real possibility of a nuclear war with global consequences. Jung indicates:

“In the individual, too, such phenomena as abnormal convictions, visions, illusions, etc. only occur when he is suffering from a psychic dissociation, that is, when there is a split between the conscious attitude and the unconscious contents opposed to it. Precisely because the conscious mind does not know about them and is therefore confronted with a situation from which there seems to be no way out, these strange contents cannot be integrated directly but seek to express themselves indirectly, thus giving rise to unexpected and apparently inexplicable opinions, beliefs, illusions, visions, and so forth. Any unusual natural occurrences such as meteors, comets, “rains of blood,” a calf with two heads, and such like abortions are interpreted as menacing omens, or else signs are seen in the heavens. Things can be seen by many people independently of one another, or even simultaneously, which are not physically real. Also, the association-process of many people often have a parallelism in time and space, with the result that different people, simultaneously and independently of one another, can produce the same new ideas, as has happened numerous times in history.” (Jung, 1964, p. 13).

In some cases, events affecting large groups of people collectively, produce almost identical effects, the visions and interpretations result very similar, mainly affecting the individuals that are the least inclined to believe in the phenomena. When this occurs, the unconscious is presented with something that is completely unknown, and it resorts to drastic measures, to be able to rationalize the perceived information. In these situations, the unconscious generates a projection, and extrapolates the information perceived into an object, that reflects some previously hidden information from the unconscious. Regarding projections, here Jung provides a very interesting comment: “Projection can be observed at work everywhere, in mental illness, in ideas of persecution and hallucinations, in so-called normal people who see the mote in their brother’s eye without seeing the beam in their own, and finally, in extreme form, in political propaganda.” (p. 14).

Projections can be found in individuals, with source in the person’s conditions, and can have deeper collective sources as well. Individual projections can be generated by personal repressions, and elements hidden in the individual’s unconscious that can become present given specific environmental triggers.

Regarding Collective projections, Jung describes:

“Collective contents, such as religious, philosophical, political, and social conflicts, select projection-carriers of a corresponding kind – Freemasons, Jesuits, Jews, Capitalists, Bolsheviks, Imperialists, etc. In the threatening situation of the world today, when people are beginning to see that everything is at stake, the projection-creating fantasy soars beyond the realm of earthly organizations and powers, into the heavens, into interstellar space, where the rulers of human fate, the gods, once had their abode in the planets. Our earthly world is split into two halves, and nobody knows where a helpful solution is to come from.” (p. 14)

Here we have presented the first approach by Jung to understand a possible source of the “flying saucer” phenomenon. While is written right after World War II and in the early stages of the cold war, we can find implications that can still be applicable today. Even with all of the technological improvements that humanity has witnessed in the past 60 years, the phenomenon remains, and the understanding of it remains more or less at the same level. We have experienced thousands more events of the phenomena, our science has given some structure to the different events by categorizing the “close encounters” according to their intensity, the extraterrestrial hypothesis remains popular, and multidimensional and time traveler possibilities have been added. Also, the possibility of all of the hypothesis being present is of consideration, but there is really not much additional real knowledge that can be presumed. The psychological conditions described by Jung so far are also still valid as a potential part of the phenomena. We will continue to analyze the rest of Jung’s works on “flying saucers” in the following writings.

References

Jung, C. G. (1964) “Flying Saucers – A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Skies” , extracted from Volume 10 of the Collected Works of C.G. Jung, “Civilization in Transition”, Bollingen Series, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

Jung’s Psychological Typology

Jung’s studies regarding the opposites made him conclude that their origin could be found in “the polaristic structure of the psyche”, a characteristic that the psyche shares with all other natural phenomena. In the introduction to Mysterium Coniuntionis, Jung describes that “Natural processes are phenomena of energy, constantly arising out of a ‘less probable state’ of polar tension. This formula is of special significance for psychology, because the conscious mind is usually reluctant to see or admit the polarity of its own background, although it is precisely from there that it gets its energy.” (Jung, 1963, pp. xvi-xvii).

Jung’s Early Views on the Mind ~ Body Relationship

On his essay Psychological Typology, written in 1936, Jung starts his analysis on the nature of opposites by discussing the mind (or soul) ~ body relationship, and introduces the concept of “temperament”, which he relates to the earlier theory of the four “humours” which are: Melancholic, phlegmatic, sanguine, and choleric, and he defines temperament as the “sum-total of emotional reactions.”

For this purpose, Jung mentions:

“The whole make-up of the body, its constitution in the broadest sense, has in fact a very great deal to do with the psychological temperament, so much that we cannot blame the doctors if they regard psychic phenomena as largely dependent on the body. Somewhere the psyche is living body, and the living body is animated matter; somehow and somewhere there is an undiscoverable unity of psyche and body which would need investigating psychically as well as physically; in other words, this unity must be as dependent on the body as it is on the psyche so far as the investigator is concerned.” (Jung, 1971, p. 545).

This description seems to leave no doubt that Jung believed some type of dual nature of the body ~ mind relationship, and that both elements maintained a complementary relationship. However, later on the same paragraph, Jung indicates:

“What proved to be a good working hypothesis, namely, that psychic phenomena are conditioned by physical processes, became a philosophical presumption with the advent of materialism. Any serious science of the living organism will reject this presumption; for on the one hand it will constantly bear in mind that living matter is an as yet unsolved mystery, and on the other hand it will be objective enough to recognize that for us there is a completely unbridgeable gulf between physical and psychic phenomena, so that the psychic realm is no less mysterious than the physical.” (Jung, 1971, p. 543).

These observations by Jung give us some clear ideas of where his understanding was at that time, in 1936.

First of all, Jung is embracing the materialistic mental model, and more importantly, he is in reality rejecting the idea of having the body ~ mind relationship representing a complementary pair. That is, Jung is indicating that body and mind are separate entities. Also, as part of his reflection, Jung admits that both the psychical and the physical are both mysteries, therefore requiring more studies.

Even more, Jung continues to reinforce his view in more detail:

“The materialistic presumption became possible only in recent times, after man’s conception of the psyche had, in the course of many centuries, emancipated itself from the old view and developed in an increasingly abstract direction. The ancients could still see body and psyche together, as an undivided unity, because they were closer to that primitive world where no moral rift yet ran through the personality, and the pagan could still feel himself indivisibly one, childishly innocent and unburdened by responsibility.” (Jung, 1971, pp. 543-544).

So this paragraph shows how Jung is definitely accepting the materialistic paradigm, at least when he wrote these words in 1936, and not only that, but Jung is also indicating that the “undivided unity” of body and mind (psyche) is the view of pagan and primitive ancestors. Here, Jung is also including in his reflections, judgements regarding religion and morality points of view, which were strong elements of the dogma of his time.

On the following paragraph of Jung’s writing, he is making an effort to strongly differentiate the ancient and primitive cultures which were dominated by their emotions, with the “philosophical man” being the civilized and advanced human that demonstrated an advanced psyche. Jung seems to be completely absorbed by his position as “educated and sophisticated member of the Western culture”, when he continues writing:

“All passions that made his (the pre-philosophical man) blood boil and his heart pound, that accelerated his breathing or took his breath away, that “turned his bowels to water” – all this was a manifestation of the “soul.” Therefore he localized the soul in the region of the diaphragm (in Greek phren, which also means mind) and the heart. It was only with the first philosophers that the seat of reason began to be assigned to the head. There are still Negroes today whose “thoughts” are localized principally in the belly, and the Pueblo Indians “think” with their hearts – “only madmen think with their heads,” they say. On this level consciousness is essentially passion and the experience of oneness. Yet, serene and tragic at once it was just this archaic man who, having started to think, invented that dichotomy which Nietzsche laid at the door of Zarathustra: the discovery of pairs of opposites, the division into odd and even, above and below, good and evil. It was the work of the old Pythagoreans, and it was their doctrine of moral responsibility and the grave metaphysical consequences of sin that gradually, in the course of the centuries, percolated through to all strata of the population, chiefly owing to the spread of the Orphic and Pythagorean mysteries.” (Jung, 1961, p. 544).

These notes by Jung seem to be some of the most biased and entitled words that attempt to describe the evolution of the body ~ mind ~ soul relationship, as well as the seat of thoughts. It is clear once again here that Jung is completely dominated by his paradigm of Western-White cultured man, to the point that his comments sound not only ignorant but quite offensive. Rather than judging and labeling the “Negroes and Indians” living in his time as “archaic” and “primitive” because the first have their “thoughts localized in the belly” and the second “think with their hearts,” it would have been more valuable to analyze this findings with an open mind, as Jung normally did, and try to understand why could this be happening with these cultures. Today, when there is evidence that the “heart brain” and the “gut brain” are real, the observations obtained by Jung from the “primitive” cultures he describes do not appear to be out of line, but instead, well ahead of their time.

The positive thoughts that can be salvaged from these paragraphs are Jung’s observation that it was “the archaic man” who invented the dichotomies and discovered the pairs of opposites, such as good and evil, above and below, and odd and even. Therefore we can determine that the action of dividing nature into pairs of opposites has been present since the time of primitive tribes in the world.

The Origins of the Dualistic Mindset according to Jung

As I have mentioned previously, one of my philosophical obsessions has been to understand the reason why we humans divide the world in pairs of opposites, and then automatically we get polarized to one of these opposites. It continues to be an interesting human condition that occurs almost in any interaction among people, and how unfortunately this tendency becomes the beginning of a conflict in which two sides of an idea are debated, with two people defending their “right to be right” and with others normally being forced to take sides and build up the opposition of ideas, again, behaviors that become automatic and end up being ego-based discussions that have a high risk of being destructive.

In the works of Carl Jung, we find that the relationship of opposites is discussed very frequently, and is a central element of his studies of the Psyche. Jung’s works seem to have the most extensive and detailed analysis of the opposites, including their impact in human’s psychology and cognitive processes. The main discussion on opposites by Jung appears in his alchemical works, being a key phenomenon that occurs as part of the union of the masculine and feminine in the Alchemical Wedding. However, it is important to describe how Jung includes the opposites relationship all over his psychological works, starting from his analysis of the origin of the opposites paradigm in the human Psyche.

The Origin of the Opposition Paradigm

In 1955-1956, at the age of eighty, Jung published one of his most important books: Mysterium Coniunctionis, with its less known subtitle: An Inquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of Psychic Opposites in Alchemy. In this book, Jung provides a synthesis of his work in Alchemy and opposites for almost 30 years, starting with his reflections on the book: The Secret of the Golden Flower, an old Chinese manuscript introduced in the West by Jung’s friend Richard Wilhelm in 1929, and later discussed in Jung’s books: Psychology and Alchemy in 1944, Alchemical Studies also in 1944, The Psychology of Transference in 1946 and Aion in 1951. A review of all of these publications by Jung will show us how the relationship of opposites is a central element of his psychology, and a key factor in all of his work.

To provide us with his idea on the origin of the dualistic paradigm in the human psyche, Jung starts his discussion on the introduction to Mysterium Coniunctionis (1963) as follows:

“But, young as the psychology of unconscious processes may be, it has nevertheless succeeded in establishing certain facts which are gaining general acceptance. One of these is the polaristic structure of the psyche, which it shares with all natural processes. Natural processes are phenomena of energy, constantly arising out of a “less probable state” of polar tension. This formula is of special significance for psychology, because the conscious mind is usually reluctant to see or admit the polarity of its own background, although it is precisely from there that it gets its energy.” (p. xvi-xvii).

Key reflections from this paragraph include the concept that “all natural processes are phenomena of energy” and natural processes and the psyche share a “polaristic structure”. Jung also indicates that energy arises from “polar tension” and the critical description of how “the conscious mind is usually reluctant to see or admit the polarity of its own background”.

So the polaristic structure originates from the energy phenomena in nature which always includes two opposite poles, such as electricity (+ and – polarities) and magnetism (+ and – poles) and the conscious mind automatically rejects and does not admit that this polarity exists in all of nature and in itself, therefore forcing consciousness to choose one of the opposites, stay tied to that pole and reject the other pole.

Jung continues with his analysis providing the following detail:

“The psychologist has only just begun to feel his way into this structure, and it now appears that the “alchemistical” philosophers made the opposites and their union one of the chief objects of their work. In their writings, certainly, they employed a symbolical terminology that frequently reminds us of the language of dreams, concerned as these often are with the problem of opposites. Since conscious thinking strives for clarity and demands unequivocal decisions, it has constantly to free itself from counterarguments and contrary tendencies, with the result that especially incompatible contents either remain totally unconscious or are habitually and assiduously overlooked. The more this is so, the more the unconscious will build up its counterposition.” (Jung, 1963, p. xvii).

This interesting paragraph by Jung is telling us how by the time he was writing Mysterium Coniunctionis between 1955—1956, the field of psychology was just starting to look into the effect of the opposites in the human psyche, a phenomena that had been largely used by the alchemists. Jung is also letting us know how the conscious mind, or “conscious thinking” is not able to manage ambiguity, which means that the rational mind has to manage the pair of opposites by choosing one of them and either “overlooking” the other or by keeping the other opposite in the unconscious. This is a key point: When faced with a pair of opposites, the psyche will choose one of them to keep in the conscious mind and the other will be maintained in the unconscious; as Jung says: “The more this is so, the more the unconscious will build up its counterposition.” Which is basically indicating that the polarization will grow stronger unconsciously. This explains how the polarizing behavior occurs: when we are presented with the opposites, based on our pre-existing mindset, we choose one opposite and automatically (unconsciously) reject the other, and we can build up the rejection to the unchosen opposite to the point of radicalization, even if is done unconsciously. If we can imagine two or more people with different mindsets or backgrounds being presented with a pair of opposites, and one of the persons chooses one of the opposites and rejects the other while the second person chooses differently, we can see how a difference of opinion and potential conflict escalation will occur since both persons will unconsciously radicalize their opposites. Since the radicalization of the rejected opposite occurs on an unconscious level, we have no immediate way to rationalize what is happening and we end up potentially in conflict with the other person. This appears to be the basis for the conflict of radicalization among individuals.

On his book: Archetype of the Absolute: The Unity of Opposites in Mysticism, Philosophy, and Psychology, Drob (2017) provides a clearer description of this process as follows:

“Jung held that consciousness and reason produce the divide between the psyche’s opposing tendencies. This is because consciousness strives for clarity and unambiguity and must therefore free itself from contrary or opposing tendencies, which it either overlooks or suppresses. As a result, consciousness identifies itself with one pole of a divide and seeks to exclude, disparage or ignore its antithesis. Thoughts, feelings, and other psychic contents that are incompatible with the determinate thread of awareness are split off from the conscious mind.” (p. 232)

Since the world is constantly presenting pairs of opposites to us, we are always choosing sides based in our conscious mindsets, which will select, or “judge” each pair of opposites based in the background, culture, education, biases, religion and even the language that we have. Both Jung and Freud identified the language as an important element of this process, which is critical to note, as we have found how language is a limiting factor in our thoughts and behaviors. And, on the other hand, the rejected opposite is constantly being kept in the unconscious, or being rejected consciously without having a rational reason for the rejection.

This seems to be the most accurate explanation as to why humans end up polarizing the opposites, and even radicalizing the rejected opposites to the point of entering into conflict with other person’s point of view. It would be very valuable if we could remember that this process is constantly happening, and being able to recognize the unconscious polarization that is happening, in order to minimize the possibility of generating unnecessary differences between people, getting radicalized and escalate the conflicts.

I will continue to discuss more of Jung’s work on the opposites in the following writings.

Compensation, Integration and Coordination of Opposites

On his description of Coincidentia Oppositorum, Jung debates on the way that the relationship between opposites can be presented. He relates the unification of opposites to the Transcendent Function which is the key for the process of Individuation. First of all, it is important to clarify the meaning that Jung gave to the concept of Individuation.

Jung’s Individuation

The term Individuation, as defined by Jung’s psychology, is a prime example of the limitations of language. If we focus strictly on the meaning of the word, it is very easy to think that Individuation should mean a process in which the person achieves individual growth to differentiate him or herself from others, or a process in which fragmentation and self are nurtured over the collective.

However, it is important to analyze the meaning of the concept according to Jung’s intentions, which will describe to us the idea of combining a process of differentiation, but also a process of understanding the whole, and the relationship of the individual to the collective, therefore being an example of Complementarity, since is defining the dual nature of individual and collective elements (the relationship of the pair of opposites individual ~ collective).

The concept of Individuation and its meaning according to Jung is a key element in Jung’s psychology, and it appears many times through Jung’s writings. Sharp (1991) gives us a very detailed description of the concept as follows:

“Individuation. A process of psychological differentiation, having for its goal the development of the individual personality…. Individuation is a process informed by the archetypal ideal of wholeness, which in turn depends on a vital relationship between ego and unconscious. The aim is not to overcome one’s personal psychology, to become perfect, but to become familiar with it. Thus individuation involves an increasing awareness of one’s unique psychological reality, including personal strengths and limitations, and at the same time a deeper appreciation of humanity in general….In Jung’s view, no one is ever completely individuated. While the goal is wholeness and a healthy working relationship with the self, the true value of individuation lies in what happens along the way.” (pp. 67-69)

The description of Individuation defined by Jung as we can see, is not a simple description of individuality, but a complex set of relationships that define some of the key elements of being human. And if we pay attention to the definition, under the paradigm of Complementarity, we can observe not just a simple relationship between just one pair of opposites, but a group of relationships that define the path for humans to achieve growth. These relationships appear to imply several complementarities which all together form the individuated human, perhaps requiring a different description for Complementarity as something more like a Super-Complementarity or a Multiple-Complementarity, since we need to observe the relationships among complementary opposites and on a second level the relationship between several complementary “pairs” of opposites.

To unpack the definition, first we have the complementary pair: ego ~ unconscious, which is a pair of elements internal to the individual’s Psique; then we see a relationship between strengths ~ limitations again related to the individual, and as an additional relationship we have the pair whole ~ individual, that provides the connection of the person to the world. The description for Individuation determines an internal wholeness of the individual with him/herself, and an external wholeness of the individual with the world, such that the goal is to achieve a higher level of internal and external wholeness in order to achieve the Individuation, bringing even one more relation of opposites to the group: internal ~ external.

Therefore, the concept of Individuation gives us a complex complementary relationship between at least 4 sets of opposite pairs:

Ego ~ Unconscious —————————— Strength ~ Limitation

Whole ~ Individual —————————— Internal ~ External

Jung does not discuss Individuation this way, but mainly makes the point that individuation consists of both an internal/individual element and an external/collective element.

In his book: Psychological Types, Jung (1971) expands on this individual/collective need of Individuation as follows:

“…only a society that can preserve its internal cohesion and collective values, while at the same time granting the individual the greatest possible freedom, has any prospect of enduring vitality. As the individual is not just a single, separate being, but by his very existence presupposes a collective relationship, it follows that the process of individuation must lead to more intense and broader collective relationships and not to isolation.” (p. 448).

While Jung describes several approaches that can be implemented to achieve the union of opposites, it appears that individuation is the main method. An important part of Individuation is the element of “compensation”, which achieves the balance and integration of the opposites. The key element of Individuation is that its process includes a complementarity between the conscious and the unconscious (Drob, 2017, p. 198). Regarding the element of compensation, Jung also mentions: “Unconscious compensation is only effective when it co-operates with an integral consciousness; assimilation is never a question of “this or that,” but always of “this and that.” (Jung, 1966, p.156). We can observe how here Jung is using directly the language of Complementarity indicating the need for and and not only or.

By itself, the process of Individuation as developed by Jung is not just a simple concept that describes a growth in maturity or the achievement of a higher level of knowledge, and even if Jung does not seem to ever provide a clear definition of Individuation, we can observe that the way the concept is presented provides with a complex set of relationships, once again, showing the relationships between several opposite individual elements and the relationships between several pairs of these opposites, all of this following Jung’s preference of using a symbolic language. Drob (2017) gives us a view of this:

“Jung’s message seems to be that as one assimilates the significance of symbolic personifications and situations, one-sided conscious attitudes are critiqued and compensated for, and the individual moves closer to assimilating the archetype of the self – an archetype that is a coincidentia oppositorum. The process of individuation involves an encounter with, and assimilation of, aspects of both the personal and collective unconscious, specifically the individual’s shadow (elements of one’s personality that the individual has hitherto ignored, rejected, and detested) and the anima or animus (the aspect of oneself that embodies characteristics opposite to those one and society associates with one’s gender). The assimilation of the shadow is illustrated in The Red Book as Jung painfully comes to “accept all,” including the most repulsive desires and tendencies within humanity and his own psyche.” (p. 199).

In this description, we can once again observe how the concept of Individuation is not just a simple relationship of two opposite elements, but a complex relationship among several elements and several pairs. At least the following pairs of opposites are defined:

Personal unconscious ~ Collective Unconscious

Self ~ Shadow

Anima ~ Animus

These pairs of elements (opposites) are engaged on a complementary relationship with each other, and then, the pairs are also engaged with each other to structure a “Complex Complementarity” of three complementary pairs of opposites in order to form the framework of individuality as defined by Jung.

One more important aspect of this structure is that Jung describes several different relationships among the opposites. First of all, a “union,” “coincidence,” “interdependence” and “harmony” of the opposites, but also a “confrontation,” or “tension.” It is not just a simple relationship of “union” that brings up the relationship of the opposites. Some additional details provided by Jung on the opposites are: “[the] identity of opposites is a characteristic feature of every psychic event in the unconscious state…there is no energy unless there is a tension of opposites and…the psyche as an “energetic system” is dependent on this very tension.” And also: “The idea here is that without the opposites (Jung cites as examples beginning and end, above and below, earlier and later, and cause and effect) nothing could be manifest.” And finally, to provide even clearer perspective on the importance of the relationship among opposites, Jung says: “Life itself is the oscillation between the tension and overcoming of opposites; when they have been completely overcome, a person (for example, the Buddha in his final reincarnation) has no further reason to live on earth.” (Drob, 2017, p. 201).

The relationships of the opposites reflected in Jung’s philosophy make us realize that this relationship is dynamic, complex and non-dualistic. It is dynamic because is ever-changing, and the oscillation between the opposites is modified with time. It is complex because is not only a relationship among a single pair of opposites, but, as we have seen, it generally involves more than one pair, and probably at any given time it might require a different number of pairs, and for the same reason, is non-dualistic, having more than just two elements to coordinate.

The dynamic characteristic of the pair of opposites behavior indicates that the whole relationship is an ongoing flow that changes with time, meaning that life in general is an ongoing flow of opposite elements organized in pairs that form complex relationships and are defining our status in life and in nature, both physically and psychically. We will continue analyzing this concept of flow, and how it can affect our psychical well-being and our growth.

Reflections on Mysterium Conunctionis and The Alchemical Wedding – The Problem of Opposites in Alchemy and Psychology

Introduction

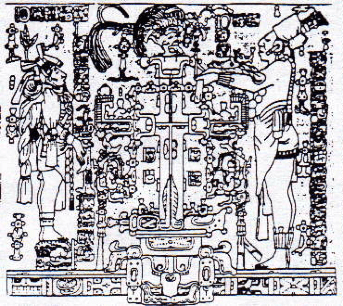

In the Foreword to Mysterium Coniunctionis, Jung describes how neurosis can be caused by dissociation of personality resulting from “the conflict of incompatible tendencies” or the problem of opposites, after repressing one of these opposites that generates only an extension of the conflict. Jung says that the therapist’s role is to have the opposites confront each other in an attempt to unite them permanently. This is a direct comparison of the process with the methods described by the alchemists. The psychological phenomenon of transference is the equivalent of the “alchemical wedding” found in the works of the alchemists. In the world of psychology, transference works to unite the opposites and eliminate neurosis, in the alchemical works the “alchemical wedding” unites the opposites of silver, feminine, the moon, with the gold, masculine and the sun, in the creation of the lapis Philosophorum or the representation of wholeness.

Since early times, humanity has seen nature with a dualistic lens, always attaching opposing labels to phenomena and human activities. We try to immediately identify if somebody is good or evil, the weather is hot or cold, etc. and we even forget sometimes that there is an infinite number of conditions between these opposite extremes. The psyche seems to be continually judging and assessing the conditions of the opposites in order to determine conditions of behavior, relationships and actions, and it is common to get to a level of conflict between the opposites that will affect the person’s psychological condition, and may result in chronic mental illnesses. Through history, there have been many philosophical, mythological and literature related works that tackle the issue of the conflict of opposites. One of these works is, the text called Aurora Consurgens, which was probably written by St. Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth century, tries to combine the alchemical view with the Christian view in regards to the problem of opposites, Jung performed extensive studies of alchemy and tried to connect the parallels of alchemy and the human psyche behavior, and as part of his studies, he included the study of Aurora Consurgens. It is even considered that Jung discovered this work in modern times.

This paper will analyze the alchemical processes of the prima materia and the alchemical wedding, and will try to identify philosophical and psychological parallels that could help in further explaining these phenomena.

The Prima Materia

Jung describes the Prima Materia as the mother of the lapis, or filius philosophorum, as being the “matter of all things”. In its feminine aspect, the prima materia is “the moon, the mother of all things, the vessel, it consists of opposites, has a thousand names, is an old woman and a whore, as Mater Alchimia it is wisdom and teaches wisdom, it contains the elixir of life in potentia and is the mother of the Saviour and of the filius Macrocosmi, it is the earth and the serpent hidden in the earth, the blackness and the dew and the miraculous water which brings together all that is divided.” In a later paragraph Jung also describes how Luna (the moon) “is on the one hand the brilliant whiteness of the full moon, on the other hand she is the blackness of the new moon, and especially the blackness of the eclipse, when the sun is darkened.” (Jung, 1963).

Marie Luis Von Franz, in her translation of Aurora Consurgens, provides the explanation that the description of wisdom is an archetypal image that plays an important role in alchemical and patristic literature. She also indicates that the tree “is primarily an image for the prima materia which gradually unfolds during the transformation process and is sufficient unto itself.” The tree is the symbol of the individuation process “in the sense of living one’s own life and thereby becoming conscious of the self.” (Von Franz, 2000).

If we focus in the concept of wisdom being represented here in metaphorical terms, we could understand how wisdom can be considered both as a provider of light to achieve positive things, but also having the potential to provide darkness when is used to achieve evil things. The fact that the prima materia here is represented as a feminine entity parallels with many other mythological stories found in almost all cultures, where there always seems to be a character represented by a woman figure or a goddess, which is represented as capable of the utmost good but also of the most terrible evil actions. This figure of the goddess is one of the main representations of the union of opposites.

In his book, Psychology of the Transference, Jung references the Rosarium, in which there is a description called the death of the royal pair as follows:

“… let the residual body, which is called earth, be reduced to ashes, from which the tincture is extracted by means of water… After this is completed, you will know that you have the substance which penetrates all substances, and the nature which contains nature, and the nature which rejoices in nature. It is named the Tyriac of the Philosophers, and it is also called the poisonous serpent, because, like this, it bites off the head of the male in the lustful heat of conception, and giving birth it dies and is divided through the midst. So also the moisture of the moon, when she receives his light, slays the sun, and at the birth of the child of the Philosophers she dies likewise, and the death of the two parents yield up their souls to their son, and die and pass away. And the parents are the food of the son…” (Jung, 1969)

An important aspect described here is the appearance of the “substance which penetrates all substances” which brings resemblance to the concept of soul. Von Franz describes the idea presented by Thomas Aquinas of the soul “not only as the ‘form’ of the body but as a form which possesses its own substantiality and also imparts it. It can act creatively on its own account and is thus an ‘ens in actu’ (actual being). Matter, in itself formless, becomes invested with its actual properties only in so far as it receives form from the soul.” (Von Franz, 2000)

This concept of a “formless matter” which takes its properties from the soul has a close resemblance to the quantum physics concept in which matter achieves a physical state only through the observation process of a conscious being, and the wave-particle duality where the initial condition is a waveform and it becomes particle only after a measurement or observation is made. Also, the concept of a “substance which penetrates all substances” seems to resemble the concept of “ether”, which in classical pre-relativistic physics was supposed to fill all the empty space, including the space between the particles that formed matter. Even though the element of “ether” was abandoned after Einstein’s theories in the early 1900’s it seems to re-appear recently as the concept of “dark matter” which is supposed to form a vast percentage of the universe.

The Paradoxes in the Conflict of Opposites

The alchemists used many paradoxes in their work with the opposites and their union. Jung describes how these paradoxes appear mostly around the “arcane substance, which was believed to contain the opposites in uncombined form as the prima material and to amalgamate them as the lapis Philosophorum.” (Jung, 1963). Jung describes more paradoxes, such as “I am the black of the white and the red of the white and the yellow of the red”, or “Burn in water and wash in fire”, or Socrates’ quotation: “Seek the coldness of the moon and ye shall find the heat of the sun, as described in Tractatus Aristotelis, the opus is said to be “a running without running, moving without motion.” And as described in The Chymical Wedding: over the main portal of the castle two words are written: “Congratulor, Condoleo.” (Jung, 1963).

In several alchemical works, the opposites appear arranged in a quaternity such as the one formed by masculine/feminine and good/evil, and the union of these opposites was the most important work of alchemy. The element that unites the opposites is Mercurius, or “the mediator making peace between the enemies or elements, that they may love one another in a meet embrace”. Mercurius is an ambivalent element, as Jung describes by quoting Dorn: “Mercurius correspond to the Holy Ghost as well as to the Anthropos; he is as Gerard Dorn says: “The true hermaphroditic Adam and microcosm”: Our Mercurius is therefore the same (Microcosm), who contains within him the perfections, virtues, and powers of Sol (in the dual sense of sun and gold), and who goes through the streets (vicos) and houses of all the planets, and in his regeneration has obtained the power of Above and Below..” (Jung, 1963). In the Manichaean doctrine of the Anthropos, the dual form of alchemy is compared with the dual form of the figure of Christ. In his dual form, there is a Christ as savior of man (Microcosm) and the form of the lapis Philosophorum as savior of the Macrocosm. One of Christ’s forms incapable of suffering (impatibilis) and takes care of souls, and the other form of Christ is capable of suffering (patibilis) having a similar role to the concept of Mercurius. The element of Sol is considered the masculine and active half of Mercurius, and while Mercurius seem to exist only as an unconscious projection, it has a “duplex” nature, having an ascending or active part called the Sol, and a passive part called the Luna, which borrows the light from the sun. Jung assumes that the human psyche is a derivative of this representation, having the diurnal life of the psyche, or consciousness, and its necessary counterpart, which is a dark, latent and non-manifested side, or the unconscious. Therefore, Jung concludes that “the duality of our psychic life is the prototype and archetype of the Sol-Luna symbolism”(Jung, 1963).

It is very interesting to analyze the way in which the human mind structures the observation of the universe and natural phenomena with a dualistic lens, which is also used when observing psychological or moral aspects of human behavior. This condition has puzzled me for a long time, and I have been trying to understand the reason why humans, at least in western cultures, tend to see nature within a dualistic paradigm. For a long time I believed that all this way of looking at the universe in current times had its origins in the Newtonian theories, and that this view was forged by the influence of the works of Descartes, Leibinitz, and others that influenced Newton with his explanation of physical phenomena. Even if these theories have been around for 300 years, It puzzled me to think that all humans in the western cultures seem to work within this paradigm, even if they have or have not studied the concepts of Newtonian Physics. It is after reading the works of Jung, and much clearly after reading the Mysterium Conunctionis and other alchemical related works, that I understand that this human approach or dualistic lens to observing nature is a clear example of an archetype. The dualistic lens that is shared universally in humans seems to be an archetype that has been the result of the influence of old traditions and mythologies in the different western cultures including the Greek and Roman traditions, that made the basis for western knowledge. In reality, the scientific works of Newton just came to bring some structure to the paradigm, and fitted well within it.

The Conjunction

The element of conjunction or “coniunctio” is the main part of the alchemical process. The alchemists were mainly concerned with the union of substances, regardless of the names used for these substances, they hoped to achieve the union and obtain the goal of the work, which was to result in gold or any other symbolic equivalent. Jung describes how these substances always had by their own nature, a numinous quality to them, “which tended towards phantasmal personification.” He indicates that these substances were like living organisms that “fertilized one another and thereby produced the living being sought by the philosophers.” The alchemists observed these substances to have hermaphroditic characteristics, and the conjunction that they were looking for was the philosophical union of “form and matter”. (Jung, 1963).

Jung reminds us that the conjunction occurs in a medium, which is represented by Mercurius, “Only through a medium can the transition take place, and Mercurius is the medium of conjunction. Mercurius is the soul (anima), which is the mediator between body and spirit.” Also, Jung indicates that Mercurius is not just the medium of conjunction but is also “that which is to be united”, being “the essence of the seminal matter of both man and woman. Mercurius masculinus and Mercurius foemineus are united in and through Mercurius menstrualis.” Jung implies that this union is also represented in the concept of the unus mundus, and psychologically in the mandala, which he indicates that “symbolizes, by its central point, the ultimate unity of all archetypes as well as of the multiplicity of the phenomenal world, and is therefore the empirical equivalent of the metaphysical concept of a unus mundus.” (Jung, 1963).

Later in Mysterium Conunctionis, Jung determines that synchronicity is the parapsychological equivalent of the concept of the unus mundus and the mandala. He indicates that “Though synchronistic phenomena occur in time and space they manifest a remarkable independence of both these indispensable determinants of physical existence and hence do not conform to the law of causality. The causalism that underlies our scientific view of the world breaks everything down into individual processes which it punctiliously tries to isolate from all other parallel processes. This tendency is absolutely necessary if we are to gain reliable knowledge of the world, but philosophically it has the advantage of breaking up, or obscuring, the universal interrelationship of events so that a recognition of the greater relationship, i.e. of the unity of the world, becomes more and more difficult.” (Jung, 1963).

Here, Jung provides us with a fascinating reflection, in which he gives the scientific method its right importance as a tool to understand the universe, but also recognizes the existence of non-causal phenomena, which do not fit inside the scientific method, and are therefore non observable by it, as well as indicating the difficulty of the observation of the “greater relationship” and unity of the world through traditional science. It is impressive to find this type of reflection, giving both views of the universe their right place and value, in a mind that is the result of the rigid and strict knowledge structure of western science.

The Opposites of Male and Female

Jung describes that the relationship of male and female is the “supreme and essential opposition”, which results from the classical alchemical trinity that comes from the male resulting from Sulphur and Mercurius and the female resulting from Mercurius and Salt, which together bring forth the “incorruptible One” or the quinta essentia. (Jung, 1963). This quinta essentia is the nature of the anima, the aqua permanens, the lapis philosophorum. It is the one and indivisible (incorruptible, ethereal, eternal).

In his book, The Psychology of the Transference, Jung writes that the link between body and spirit is hermaphroditic, i.e. a coniunctio Solis et Lunae. Jung indicates that “Mercurius is the hermaphrodite pair par excellence. From all this it may be gathered that the queen stands for the body and the king for the spirit, but that both are unrelated without the soul, since this is the vinculum which holds them together. If no bond of love exists, they have no soul. In our pictures the bond is effected by the dove from above and by the water from below. These constitute the link – in other words, they are the soul. Thus the underlying idea of the psychic proves it to be a half bodily, half spiritual substance, an anima media natura, as the alchemists call it, an hermaphroditic being capable of uniting the opposites, but who is never complete in the individual unless related to another individual. The unrelated human being lacks wholeness, for he can achieve wholeness only through the soul, and the soul cannot exist without its other side, which is always found in a “You”. Wholeness is a combination of I and You, and these show themselves to be parts of a transcendent unity whose nature can only be grasped symbolically, as in the symbols of the rotundum, the rose, the wheel, or the coniunctio Solis et Lunae.” (Jung, 1969).

In the Alchemical Wedding of Christian Rosycross, the concept of the inversely proportional polarization of man and woman is discussed. It is said that “the vehicles of the male personality are differently polarized from those of the female: the mental body of the man is negatively polarized while that of the female is positively polarized: the astral body of the man is positively polarized, while that of the female is negative; the etheric body of the man is negatively polarized, while that of the woman is positive; and the physical body of the man is positively polarized, while that of the woman is negative. Given these conditions, it is clear that the two sexes need each other “absolutely, and must develop an extremely intelligent cooperation, so that their two areas of activity may merge harmoniously. This cooperation must unfold the norms of love and virtue….”. Also, this work points out that one of the meanings of the short stories and riddles in The Alchemical Wedding, is that many unbreakable karmic threads are woven in the course of human life through which people are drawn to each other and by which they are obliged to take certain decisions and courses of action. In all these cases the worthy candidate of the gnostic mysteries will decide on that standpoint and that course of action in which the self is always made subservient, in whatever way, to the highest interests of the other person involved, in accordance with the norms of the mysterious virtue. If you keep this law, you will transform all the sorrow you may experience on account of any limited material sacrifice to a high, serene joy. For all suffering is but temporary, while the victory of the soul is eternal.” (Van Rijckenborgh, 1991).

If we look at the relationship between male and female in the way Jung describes it as the supreme conflict of opposites, and their union can represent the ultimate level of achievement, we could relate this somewhat to Freud’s thought that humans motivation is basically sexual. In Jung’s theory, however, sex is only one part of the whole and the union needs to include the mind, spirit and soul, which means it is a union of a much higher level but at the same time is much more complicated to achieve. On the other hand, Jung separates the male and female opposites and describes in a simple way the union of these ‘pure’ opposites, but now we understand that each individual has both a male and female element, which makes the union of two individuals much more difficult, given that these opposites are not pure, but are a combination of both, and also are possibly changing within the individual as well. The condition of both male and female elements being present in the individual could very possibly account for some psychotic conditions, but most importantly, the conflict between the male and female opposites is much more complicated given the ever changing combination of male/female or right brain/left brain elements in the individual.

It seems that the conflict begins within each individual before it is transferred to external conflicts. The unus mundus condition is to be achieved individually and then with the external partner. The complementarity achieved by maintaining the internal balance and then achieving the external balance with the partner seems to be the way to find the wholeness expressed as the communion of “I” and “YOU”.

Conclusion

In Jung’s study of the alchemical works we can see several powerful ideas, both for therapy use as well as for a philosophical understanding of nature. While Jung uses a traditional dualistic lens, he brings into the picture the importance of everything in relationship to each other, as a whole. The union of the opposites and the description of how the male and female opposite union is the ultimate goal to achieve the equivalent of the alchemical goal, seems to represent the center of the psychological process of humans and of nature itself. There are many parallels from the concepts presented by Jung and the authors of alchemical works with the ideas of modern physics. Particularly the union of opposites and its relationship to concepts in quantum physics such as Bohr’s complementarity are worth to analyze more, and are excellent dissertation materials.

References

Jung, C. G. (1963). Mysterium Coniunctionis, Volume 14 of The Collected Works, Bollingen Series XX. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

Jung, C. G. (1969). The Psychology of Transference. New York, NY: Routledge

Thomas, Aquinas, Saint (1225?) AURORA CONSURGENS, a document attributed to Thomas Aquinas on the Problem of Opposites in Alchemy. Edited by Marie-Louise Von Franz. Toronto, Canada: Inner City Books

Van Rijckenborgh, J. (1991) The Alchemical Wedding of Christian Rosycross. Esoteric Analysis of the Chymische Hochzeit Christiani Rosencreutz Anno 1459. Haarlem, The Netherlands: Rosekruis Pers

Jung on Opposites: Alchemical and Psychological Views

As mentioned before, much of Jung’s work is focused in analyzing the relationship of opposites. The way that the tension of opposites affect the human psyche was one of Jung’s main obsessions, both in his professional life as well as in his own personal struggles with depression and psychosis. Jung used several alchemical concepts to analyze the opposites and study their parallel with the human psyche. Some of the concepts found in Jung’s works are: unio mystica – mystic or sacred marriage, complexio oppositorum – opposites embodied in a single image, unus mundus – one world, coincidentia oppositorum – coincidence of opposites, the Philosopher’s Stone, and the coniunctio.

The Coniunctio

The concept of coniunctio is mainly found in Jung’s book: Mysterium Coniunctionis, as mentioned before written between 1955 and 1956. The description of the coniunctio as provided by Sharp (1991) as follows: “… literally ‘conjunction,’ used in alchemy to refer to chemical combinations, psychologically, it points to the union of opposites and the birth of new possibilities.” (p. 42).

Sharp also provides the reference to Jung’s description:

“The coniunctio is an a priori image that occupies a prominent place in the history of man’s mental development. If we trace this idea back, we find it has two sources in alchemy, one Christian, the other pagan. The Christian source is unmistakably the doctrine of Christ and the Church, sponsus and sponsa, where Christ takes the role of Sol and the Church that of Luna. The pagan source is on the one hand the hieros-gamos, on the other the marital union of the mystic with God.” Jung (1966).

The concept of hieros-gamos mentioned in this paragraph is also widely found in Jung’s works and it is a Greek term that means “sacred marriage.”

On the introduction to Mysterium Coniunctionis, Jung starts by indicating that “The factors which come together in the coniunctio are conceived as opposites, either confronting one another in enmity or attracting one another in love.” (Jung, 1963), following by a list of the main pairs of opposites used in the alchemical work:

Humidum (moist)/Siccum (dry) Frigidum (cold)/calidum (warm)

Superiora (upper, higher)/inferiora (lower) Spiritus-anima(spirit-soul)/corpus (body)

Coelum (heaven)/terra (earth) Ignis (fire)/aqua (water)

Bright/dark Agens (active)/patiens (passive)

Volatile (volatile, gaseous)/fixum (solid) Pretiosum (precious, costly)/vile (cheap, common)

Bonum (good)/malum (evil) Manifestum (open)/occultum (occult)

Oriens (east)/occidens (west) Vivum (living)/mortuum (dead)

Masculus (masculine)/foemina(feminine) Sol/Luna

Jung describes how these pairs of opposites form a “dualism” and “…often the polarity is arranged as a quaternio (quaternity), with the two opposites crossing one another, as for instance the four elements of the four qualities (moist, dry, cold warm), or the four directions and seasons, thus producing the cross as an emblem of the four elements and symbol of the sublunary physical world.” (Jung, 1963, p. 3).

The quaternity described by Jung is also found later on his concept of mental functions, in which the quaternity is formed by the two pairs of opposites: thinking ~ feeling and sensation ~ intuition, as well as the attitude type duality of: introversion ~ extraversion. These elements are present on every individual’s personalities in different levels, and some of their parts being in the conscious while other parts are present in the unconscious. If we observe the distribution of all these elements, we can define several complementary relationships between the individual elements, and then a second level of complementarity between the pairs, where the higher level of complementarity is formed by the conscious ~ unconscious.

This demonstrates us that complementarity is not just a simple relationship between a pair of opposites, but can expand into multi-level complementarities. As is the case with most every phenomena in nature, complementarity as seen by just being formed by one pair of opposites provides a very reductionistic view, and the reality of the relationships found is much more complex.

Opposite Attitudes

When analyzing the problems that arise from the polarization of the opposites, Jung was able to study this concept and to personally live its reality during the rise of Nazism in Germany. First of all, Jung was able to find that regarding the two attitudes of introversion and extroversion, one of them normally dominates the individual conscious experience and behavior while the other takes a compensatory (or complementary) position in the individual’s unconscious. The balance between these attitudes is changing constantly, even if one of the attitudes is dominant during normal conditions. There might be some influence or trigger (Jung does not mention if this can be internal or external, but most probably could be either) that may generate an unexpected, distressing, or impulsive thought or behavior (Drob, 2017, p. 208).

Drob (2017) has more details on this regard when he mentions:

“…each individual has both a conscious and unconscious attitude – the latter often appearing in fantasy and dreams. At times the two attitudes intermingle and it becomes difficult to ascertain which is conscious and which is unconscious. Conscious attitudes and functions dominate the individual’s experience and behavior unless and until they become over-emphasized, causing a compensatory drive to be set in motion by one’s opposing unconscious attitudes and functions.” (p. 208)

Before we get to discuss more details about Jung and his views on Nazism, we will prepare a framework to try and structure the conditions expressed here. First of all, we have discussed the introvert ~ extrovert pair of opposites, which has also mentioned as internal ~ external attitude related pair of opposites. This seems to be the beginning of an attempt to structure the attitude related sources using a reductionistic approach. While Jung always showed an open mind and was conscious of the risks of polarization, he obviously was embedded in the mechanistic paradigm, and would have to maintain some level of polarization tendencies, whether consciously or unconsciously. This is a risk that remains to this day in all of us, and we have to make an effort to observe when we are polarizing our thoughts. The full open-minded approach to maintain a balance between two opposites does not come easy to us.

A potential evolution of these (complementary) dichotomies can be expressed as follows:

Attitude towards a certain condition:

Internal ~ External (Reaction)

Introverted ~ Extroverted (Tendency)

Conscious ~ Unconscious (Reaction)

And to align these “Jungian” pairs of opposites with McGilchrist’s work we can continue the analysis with the following complementary pairs of opposites:

Jung ~ McGilchrist

Apollo ~ Dionysius (Archetype)

Reason ~ Transcendence

Self Mastery ~ Self Abandon

Left Hemisphere ~ Right Hemisphere